Monday, November 23, 2020

Wednesday, May 06, 2020

Tuesday, May 05, 2020

Monday, May 04, 2020

Sunday, May 03, 2020

Math 402 (spring 2020): Surface Integrals

Here are parameterizations of the cone written out in detail. (The double-bar for vector magnitude was the notation we were using when I first wrote this up. Stewart uses single-bar notation, like absolute value bars.) As you can see, the video illustrates the second approach.

Saturday, May 02, 2020

Math 402 (spring 2020): Green's Theorem

The solutions below demonstrate different solutions to the problem solved in the video. Note that Green's Theorem can be used only when the field F is planar and the path C is closed. As you can see, different solutions may work just fine, but this is an example where simply doing the line integral (and skipping Green's Theorem) is not recommended.

Friday, May 01, 2020

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

Sunday, April 26, 2020

Thursday, April 23, 2020

Wednesday, April 22, 2020

Monday, April 20, 2020

Friday, April 17, 2020

Wednesday, April 15, 2020

Tuesday, April 14, 2020

Sunday, April 12, 2020

Saturday, April 11, 2020

Wednesday, April 01, 2020

Tuesday, March 31, 2020

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Friday, March 27, 2020

Thursday, March 26, 2020

Math 402 (spring 2020): Lagrange Multipliers

Note: If two vectors are multiples of each other (i.e., parallel), it's completely arbitrary which side of the equation gets the scalar coefficient: λ∇f = ∇g is just as good as ∇f = λ∇g.

Stat 300: Hypothesis Testing

Note: x-bar is 7.46, but 7.45 is accidentally written down at first. Sorry!

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Monday, March 23, 2020

Sunday, March 22, 2020

Friday, March 20, 2020

Friday, March 13, 2020

Tuesday, March 10, 2020

A primer on polling

Pollsters usually examine a sample that is much smaller than the actual

population in question. For a statewide election in California, for

example, a pollster is likely to interview a few hundred voters to

discover the opinions of an electorate that comprises millions. How can

this possibly work?

A sample example

A small sample can give you a surprisingly robust measure of what is going on with a large population. As long as the pollster takes some practical measures to ensure that a sample is not unduly skewed (don't find all your polling subjects in the waiting rooms of Lexus dealerships!), the sample will be representative of the whole population. That's why you'll hear people talk about picking people at random in a polling survey. It's a way to avoid biasing a sample.

Suppose, for the sake of illustration, that a voting population is evenly divided between candidates A and B. Suppose that you're going to pick two voters at random and ask them who they prefer. What could happen?

There are actually four possible outcomes: Both subjects prefer A, both subjects prefer B, the first subject prefers A while the second prefers B, and the first subject prefers B while the second prefers A. These four outcomes are equally likely, leading us to an interesting conclusion: Even a sample of size 2 gives you a correct measure of voter preference half the time!

No doubt this result should improve if we choose a larger sample. After all, while it's true that half of the possible outcomes correctly reflect the opinions of the electorate, the other half is way off, telling us there is unanimous sentiment in favor of one candidate.

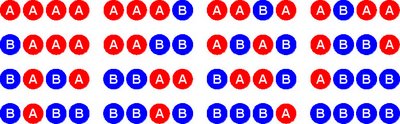

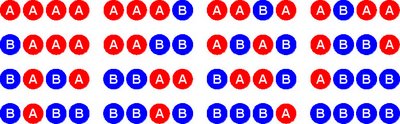

Let's poll four voters this time. There are actually sixteen (24) equally likely results:

This time, six of the possible sample results (that's three-eighths) are exactly right in mirroring the fifty-fifty split of the electorate. What's more, only two of the possible samples (one-eighth of them) tell us to expect a unanimous vote for one of the candidates. The other samples (three-eighths of them) give skewed results—giving one candidate a three-to-one edge over the other—but not as badly skewed as in the previous two-person sample.

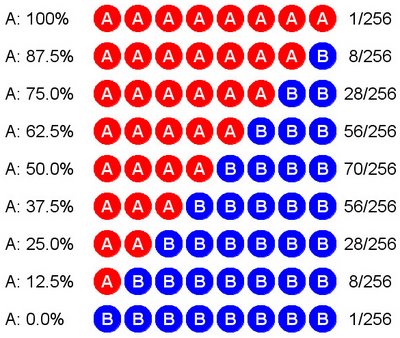

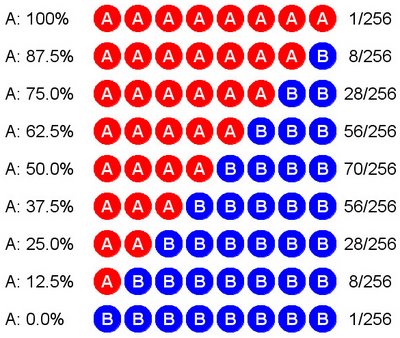

You know what's going to happen as we continue to increase the sample size: It's going to get more and more difficult to obtain really unrepresentative results. Let's look at what occurs when we increase the sample size to just eight randomly selected voters. There are 28 = 256 ways the samples can come up, varying from all for A to all for B. Okay, that's too many cases to write out individually. We'll have to group them. The following table summarizes the possibilities. For example, there are 28 cases in which we end up with 6 votes for A versus 2 for B. (In case you're curious, these numbers come from binomial coefficients, made famous in Pascal's triangle.) Check it out:

As

you can see, in each case I've given the percentage of supporters for A

found in the sample. There are 56 samples in which A has 62.5% support,

70 in which A has 50% support, and 56 in which A has only 37.5%. In

this little experiment, therefore, we have 56 + 70 + 56 = 182 cases out

of 256 in which A has support between 37.5% and 62.5%. Since 182/256 ≈

71%, that is how often our random sample will indicate that A's support

is between 37.5% and 62.5%. Observe that 37.5% = 50% − 12.5% and 62.5% =

50% + 12.5%. Since we set this up under the assumption that A's true

support is 50%, our poll will be within ±12.5% of the true result about

71% of the time. Mind you, we have no idea in advance which type of

sample we'll actually get when polling the electorate. We're playing the

percentages, which is how it all works.

As

you can see, in each case I've given the percentage of supporters for A

found in the sample. There are 56 samples in which A has 62.5% support,

70 in which A has 50% support, and 56 in which A has only 37.5%. In

this little experiment, therefore, we have 56 + 70 + 56 = 182 cases out

of 256 in which A has support between 37.5% and 62.5%. Since 182/256 ≈

71%, that is how often our random sample will indicate that A's support

is between 37.5% and 62.5%. Observe that 37.5% = 50% − 12.5% and 62.5% =

50% + 12.5%. Since we set this up under the assumption that A's true

support is 50%, our poll will be within ±12.5% of the true result about

71% of the time. Mind you, we have no idea in advance which type of

sample we'll actually get when polling the electorate. We're playing the

percentages, which is how it all works.

These results are pretty crude, since professional polls do much better than ±12.5% only 71% of the time, but we did this by asking only eight voters! A real poll would ask a few hundred voters, which suffices to get a result within ±3% about 95% of the time. That's why pollsters don't have to ask a majority of the voters their preferences in order to get results that are quite accurate. A relatively small sample can produce a solid estimate.

Bigger may be only slightly better

It's unfortunate that more people don't take a decent course in probability and statistics. That's why most folks are mystified by polls and can't understand why they work. They do work, as I've just shown you, within the limits of their accuracy. Pollsters can measure that accuracy and publish the limitations of their polls alongside their vote estimates. Every responsible pollster does this. (Naturally, everything I say is irrelevant when it comes to biased polls that are commissioned for the express purpose of misleading people. One should always treat skeptically any poll that comes directly from a candidate's own campaign staff.)

The controversy over sample size is constantly hyped by the statistically ignorant. More than fifty years ago, Phyllis Schlafly was harping on the same point:

By the way, did you notice that Mervin Field's sample size was a power of 2? It would have occurred in the natural progression of samples that I modeled for you in our polling experiment. In my three different sampling examples, I doubled the sample size each time, going from 2 to 4 to 8, each time getting a significant increase in reliability. If you keep up the pattern, you get 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256. As you can see, Field went way beyond my little experiment, doubling my final sample of 8 an additional five times before he was satisfied he would be sampling enough voters for a good result.

Two caveats

There are a couple of things I should stress about the polling game we just played. First, of course, in real life we would not know the exact division of the voters beforehand. That's what we're trying to find out. It won't usually be something as nice and neat as fifty-fifty. However, as long as there's a real division between voters (in other words, not some 90% versus 10% rout), it won't be too difficult to poll enough voters to get an accurate profile.

Second, even a poll that is supposed to be within its estimated margin of error 95% of the time will be wrong and fall outside those bounds 5% of the time. That's one time in twenty. Therefore, whenever you see a political poll whose results seem way out of whack, it could be one of those flukes. Remember, polling is based on probability and statistics: it's accurate in the long run rather than in every specific instance. In a hot contest where lots of polls are taken, a candidate's campaign is likely to release only those polls that show the candidate in good shape. The 5% fluke factor may be just enough to keep hope alive among those people who believe everything they read.

Pollsters take their results with a grain of salt, so you should, too. But it's not because of sample size.

A sample example

A small sample can give you a surprisingly robust measure of what is going on with a large population. As long as the pollster takes some practical measures to ensure that a sample is not unduly skewed (don't find all your polling subjects in the waiting rooms of Lexus dealerships!), the sample will be representative of the whole population. That's why you'll hear people talk about picking people at random in a polling survey. It's a way to avoid biasing a sample.

Suppose, for the sake of illustration, that a voting population is evenly divided between candidates A and B. Suppose that you're going to pick two voters at random and ask them who they prefer. What could happen?

There are actually four possible outcomes: Both subjects prefer A, both subjects prefer B, the first subject prefers A while the second prefers B, and the first subject prefers B while the second prefers A. These four outcomes are equally likely, leading us to an interesting conclusion: Even a sample of size 2 gives you a correct measure of voter preference half the time!

No doubt this result should improve if we choose a larger sample. After all, while it's true that half of the possible outcomes correctly reflect the opinions of the electorate, the other half is way off, telling us there is unanimous sentiment in favor of one candidate.

Let's poll four voters this time. There are actually sixteen (24) equally likely results:

This time, six of the possible sample results (that's three-eighths) are exactly right in mirroring the fifty-fifty split of the electorate. What's more, only two of the possible samples (one-eighth of them) tell us to expect a unanimous vote for one of the candidates. The other samples (three-eighths of them) give skewed results—giving one candidate a three-to-one edge over the other—but not as badly skewed as in the previous two-person sample.

You know what's going to happen as we continue to increase the sample size: It's going to get more and more difficult to obtain really unrepresentative results. Let's look at what occurs when we increase the sample size to just eight randomly selected voters. There are 28 = 256 ways the samples can come up, varying from all for A to all for B. Okay, that's too many cases to write out individually. We'll have to group them. The following table summarizes the possibilities. For example, there are 28 cases in which we end up with 6 votes for A versus 2 for B. (In case you're curious, these numbers come from binomial coefficients, made famous in Pascal's triangle.) Check it out:

As

you can see, in each case I've given the percentage of supporters for A

found in the sample. There are 56 samples in which A has 62.5% support,

70 in which A has 50% support, and 56 in which A has only 37.5%. In

this little experiment, therefore, we have 56 + 70 + 56 = 182 cases out

of 256 in which A has support between 37.5% and 62.5%. Since 182/256 ≈

71%, that is how often our random sample will indicate that A's support

is between 37.5% and 62.5%. Observe that 37.5% = 50% − 12.5% and 62.5% =

50% + 12.5%. Since we set this up under the assumption that A's true

support is 50%, our poll will be within ±12.5% of the true result about

71% of the time. Mind you, we have no idea in advance which type of

sample we'll actually get when polling the electorate. We're playing the

percentages, which is how it all works.

As

you can see, in each case I've given the percentage of supporters for A

found in the sample. There are 56 samples in which A has 62.5% support,

70 in which A has 50% support, and 56 in which A has only 37.5%. In

this little experiment, therefore, we have 56 + 70 + 56 = 182 cases out

of 256 in which A has support between 37.5% and 62.5%. Since 182/256 ≈

71%, that is how often our random sample will indicate that A's support

is between 37.5% and 62.5%. Observe that 37.5% = 50% − 12.5% and 62.5% =

50% + 12.5%. Since we set this up under the assumption that A's true

support is 50%, our poll will be within ±12.5% of the true result about

71% of the time. Mind you, we have no idea in advance which type of

sample we'll actually get when polling the electorate. We're playing the

percentages, which is how it all works.These results are pretty crude, since professional polls do much better than ±12.5% only 71% of the time, but we did this by asking only eight voters! A real poll would ask a few hundred voters, which suffices to get a result within ±3% about 95% of the time. That's why pollsters don't have to ask a majority of the voters their preferences in order to get results that are quite accurate. A relatively small sample can produce a solid estimate.

Bigger may be only slightly better

It's unfortunate that more people don't take a decent course in probability and statistics. That's why most folks are mystified by polls and can't understand why they work. They do work, as I've just shown you, within the limits of their accuracy. Pollsters can measure that accuracy and publish the limitations of their polls alongside their vote estimates. Every responsible pollster does this. (Naturally, everything I say is irrelevant when it comes to biased polls that are commissioned for the express purpose of misleading people. One should always treat skeptically any poll that comes directly from a candidate's own campaign staff.)

The controversy over sample size is constantly hyped by the statistically ignorant. More than fifty years ago, Phyllis Schlafly was harping on the same point:

While her math is okay, Schlafly doesn't know what she's talking about. A sample size of 256 is quite good and should have produced a reliable snapshot of voter sentiment at the time the poll was conducted. In addition to getting the pollster's name wrong (it's Mervin), Schlafly neglected to mention that Rockefeller's wife had a baby just before the California primary, sharply reminding everyone about his controversial divorce from his first wife. You can't blame a poll for not anticipating a development like that. Otherwise, Schlafly's complaint about the poll is based on her ignorance about the sufficiency of sample sizes.The unscientific nature of the polls was revealed by Marvin [sic] D. Field, formerly with the Gallup poll and now head of one of the polls which picked Rockefeller to beat Goldwater in the California primary, who admitted to the press that he polled only 256 out of the 3,002,038 registered Republicans in California. He thus based his prediction on .000085 of Republican voters.

By the way, did you notice that Mervin Field's sample size was a power of 2? It would have occurred in the natural progression of samples that I modeled for you in our polling experiment. In my three different sampling examples, I doubled the sample size each time, going from 2 to 4 to 8, each time getting a significant increase in reliability. If you keep up the pattern, you get 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256. As you can see, Field went way beyond my little experiment, doubling my final sample of 8 an additional five times before he was satisfied he would be sampling enough voters for a good result.

Two caveats

There are a couple of things I should stress about the polling game we just played. First, of course, in real life we would not know the exact division of the voters beforehand. That's what we're trying to find out. It won't usually be something as nice and neat as fifty-fifty. However, as long as there's a real division between voters (in other words, not some 90% versus 10% rout), it won't be too difficult to poll enough voters to get an accurate profile.

Second, even a poll that is supposed to be within its estimated margin of error 95% of the time will be wrong and fall outside those bounds 5% of the time. That's one time in twenty. Therefore, whenever you see a political poll whose results seem way out of whack, it could be one of those flukes. Remember, polling is based on probability and statistics: it's accurate in the long run rather than in every specific instance. In a hot contest where lots of polls are taken, a candidate's campaign is likely to release only those polls that show the candidate in good shape. The 5% fluke factor may be just enough to keep hope alive among those people who believe everything they read.

Pollsters take their results with a grain of salt, so you should, too. But it's not because of sample size.

Tuesday, March 03, 2020

Saturday, February 29, 2020

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)